“Procrastination is the art of keeping up with yesterday.”Don Marquis

It seems only reasonable that the first (and possibly only, I’m really not doing well with this blog lark recently) post of 2014 consists of some editorial that leads to my latest set of excuses as to why my iPhone game is still not completed. And you know what they say about excuses: your friends don’t need them and nobody else cares. This way, though, we can all look back and laugh later in the year when my new set of plans predictably turn out to be massively overoptimistic due to a combination of work, children and a desire to be in the garden burning sausages and burgers rather than doing level design. But depressing realism aside, let’s kick off with what everybody has been waiting for: 2014’s first piece of cobra-art!

Look! Pigs flying! Blue moon! Daughter-friendly artwork! Honestly, it’s three levels of win and you know it. Plus it’s the best indication of the conditions required for my game to be released.

Having successfully sneaked into a job in the games industry in the early 90s, my first three published games were pretty much entirely programmed by me. Largely, I did the design work, too (although goodness only knows how obscurely rubbish they’d have been without the input of those considerably more experienced than me). Needless to say, though, I didn’t draw the graphics. They were Amiga games and it was amazing to be in a position to be the whole programming team. There’s an incredible satisfaction from knowing that you did it. It was yours. You were not “programmer 5” on some large team, three other people hadn’t told you what to do, you’d architected the system, solved all the problems and delivered the tens of thousands of lines of lovingly crafted 68000 assembly language code that made it happen. Then, it is actually shipped: it’s a real box, on real shelves and you get both the horror and joy of reading reviews in magazines (that’s right, I’m that old, it was magazines back then). It’s a wow factor and express learning experience that largely faded out as the 90s dragged on. As cost and complexity of development grew, self-publishing became almost impossible without a massive marketing budget and bar the odd surprise, the “indie game developer” faded into mythology: exaggerated drunken stories told in the bar at conferences like GDC and E3.

Then something amazing happened. The iPhone appeared.

Suddenly, one programmer could repeat what happened in the 80s: write a game. From scratch. And publish it. And that’s without the need to sell one’s soul, bend over backwards, yield to other opinions or have to listen to ill-considered focus groups1, wear animal noses2 or pack products into four magical marketing boxes3. And that enabled innovation on truly magnificent levels. Whole new gaming genres, wonderfully endearing ideas and genuinely different things. Pretty things. Things that the massive inertia of the larger companies generally prevents by beating them to death with procedures (or “risk management” as I’ve heard it called) — I suspect most bright-eyed designers who’ve entered a large gaming company have watched sadly and with growing despair as each and every idea they have is gradually diluted through every step of the green-light committees until, mysteriously, the cup of joy is empty.

The nimble adapt to the changing world

This last five years or so has been an extraordinary repeat of something few thought would ever happen again — the bedroom programmer — and, whatever you think of Apple, we largely have them to thank for it happening so soon and with such success. Sure, someone else would have managed it eventually, but Apple made it easy. Made it enjoyable. Made it so that one person could do it. Without a team. Without a huge budget. Hell, I’d kiss each and every one of them for what they did, with tongues. Their efforts created an unexpected easy publisher-free route to market and shone a deserved light on the wonderful achievements of small independent developers, on all platforms, that hadn’t really been seen since the 80s. This opportunity has been a mini gaming cambrian explosion: in come minds untarnished by what the big corporates believe is “the right way” and out of those minds come strange new wonders.

The world has clearly changed dramatically. We carry our gaming, music, video and networking and telecommunications device around with us and it is just that: a single device, not an assortment of devices as it was just a few years ago. It’s transformations of this magnitude that make Nintendo’s Wii-U and 3DS feel like totally baffling products… I can’t help but wonder if they’d be better off as a software company delivering their unique gameplay experiences to platforms whose owners have a better grasp of the changing world than they do. It would seem that the whole traditional console business is at risk because today’s connected gaming habits have simply overtaken it: adding multiple screens and attempting to spread beyond a device that plays games and does it well seems like a foolish step into a future that won’t take kindly to second best.

Microsoft seem oddly detached from this change too: their obsession with performance-per-watt unfriendly heavy high-level languages and frameworks makes no sense for mobile devices until battery technology makes a good few leaps forwards. Perhaps this is why C++ is now “in” again at Castle Microsoft. Then there’s the device-in-the-living room XBone:

- The name. “Ecks-bee-one” sounds like XBOX 1, not XBOX 3, which technically it is. It is an odd confusion for them to inflict on themselves and their users to have a new device that is pronounced the same way as the original

- The Kinect. As cool as it is, and it is cool, the forced purchase and the not-quite-always-on camera feels a little creepy. The same sort of creepy loved by “Smart” TV manufacturers (Samsung and LG, I’m looking at you, because you’re probably looking at me, somehow)

- What is it? The big media box in the living room was a battle that was fought, lost and won by nobody. The living room’s focus has shifted from the ‘ultimate set top box’ to everyone’s individual screens and whilst a games box is easy to understand, an über do-it-all media box is less understandable to today’s modern living room inhabitants

Still, everyone’s an expert, and as fun as armchair generalling is, it’s always done with less than half the story and considerably less than half the expertise. Plus I’m digressing, but I’m mad at Microsoft at the moment for their outrageous Visual Studio pricing strategy: my reward for buying version after version of Visual Studio (since version 4) is, it appears, nothing at all (cue stupid sexy Flanders animation). I want C++, not C# and a whole pile of other junk, and I certainly don’t feel that over £500 is a reasonable price for a compiler. But as Joel Spolsky so elegantly explained a decade ago, pricing is both variable and a black art and I’d assert that independent small developers sit at the worst possible place on the pricing curve because they have the least amount leverage. Developers-developers-developers my arse.

No, I am not missing the irony of not getting to the point

But windows of opportunity like this don’t remain open forever. Autumn comes. Then it closes gradually until eventually it’s shut. Curtains drawn, it’s all over until the next time that disruptive new technologies, products and processes enable the individual to leave the incumbents dazed, confused and stationary. And that window is closing now. Creating a new game from scratch from thin air to on-the-market for the individual is getting harder every day and soon it’ll be pretty much impossible to all but the exceptionally gifted or lucky few. The big boys are drowning out the small guys with massive marketing budgets and, more often than not, quantity over quality. Models like Freemium are sucking the will to live out of developers who find it almost impossible to get right and bloody expensive to support. Besides which, it’s too easy to fall onto the cynical dark side and end up spending more effort on figuring out how to scam your users than delivering any actual gameplay.

Conspiring alongside business models and crowded markets are the platforms themselves. They’re rapidly growing in complexity, they’re fragmenting, the developer tools are overwhelming to the beginner, the hardware requires considerably more knowledge to get anything useful out of it and the whole process of bringing a product to market is tougher. It’s hard to spot a needle in a haystack and the world’s various app-stores are increasingly massive haystacks. Effective social media use goes a long way, but it’s a crowded market and incredibly hard work: unless you’re coming to it with something unbelievably special it’s going to be a real challenge to gain marketing traction without a budget or a publisher. To put it another way, the 80s are rolling into the 90s again but two decades further down the line – it’s a cycle, and it’s currently cycling.

No, there’s not always tomorrow

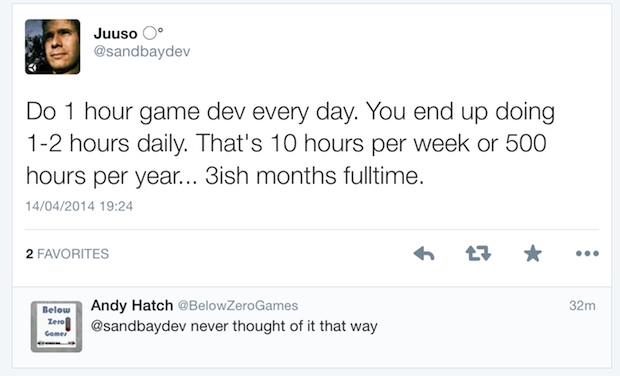

So if you have dreams of being an indie developer and publishing a mobile game of your own, now is the time to do it. Before it is too late. And it soon will be for all but the very fortunate few. Find the time. Make it happen. You’ve probably got, oh, a year, two years tops, but set your expectations low: you’re more likely to find a pot of gold in your back yard than you are to make a mint from releasing a game as an independent developer. In case you can’t read between the lines: do it for the fun and have fun doing it or you’re almost certainly wasting your time. I, like most with such indie ideas, am a steaming hypocrite because I’ve been idly working on my iPhone game for years finding one reason or another why I can’t spare ten minutes here and there to make some progress. The one area I have made progress with is my procrastination skills: they’re second to none. However, the acute awareness that the window of opportunity is slimmer than the population of flatland is beginning to weigh on my mind. There’s a dream here, and I don’t want it to be merely a dream.

As the author of this tweet knows very well, it is at least a trillion times easier to say this than it is to do. I STILL can’t work out if the reply is sarcasm of such subtlety that it is beyond my comprehension skills.

My desire to publish an iPad/iPhone game or two is not because I think I’ll be driving over the horizon in my Aston Martin with an evil laugh echoing from between sacks of money, but because I just want to know that I’ve done it. It’s one item on a checklist that’s longer than Mr Tickle’s arms. That’s right, both of them. Besides which, I’m planning on releasing the first game for free (as in “real free”, not “ad-supported privacy sucking ‘free'”), so if it breaks even it will be because I have twisted the fundamental laws of the universe itself. At this stage, this is purely an exercise in laying solid foundations: just so I know I can still do this stuff and because it builds the technology I require to… go further.

Oh, there will be other windows, but they’ll be different, and maybe I’ll not fancy being part of them or maybe they’ll simply be beyond where my skills lie. Who knows what the next opportunity will be: perhaps it’ll be related to 3D printers, or maybe Google Glass and the Oculus Rift VR headset offer tantalising glimpses into an incredibly exciting future of human-computer-interaction that, finally, doesn’t involve keyboards, mice or any other ridiculously computer friendly junk. Maybe the new era of playing nice with the intelligent part of the equation, the human, is closer than we might have dreamed. But it’s hard to imagine how I’d fit into all this because nobody knows how it’ll pan out. Glass and VR headsets are all fine and dandy, but the killer-device, the real disruptive market-changer is, in my opinion, neither: let’s face it, nobody really wants to wear that stuff. Slap screens on contact lenses and then we’re talking: it’ll transform augmented reality, reduce the size of VR setups to just a pile of sensors and have the added advantage of stopping Glass type product users from walking around looking like robots with “rob me” stickers on their backs. Besides which, with a cycle interval of a couple of decades or so, my time is running out; perhaps allowing this one to slam on my fingers would be a thing of great regret unless by some stroke of good fortune bottom-up, biologically inspired simulations roll up as the only way of managing the future’s insane software complexity. (As an “interesting” footnote, I find it’s interesting that in this article, that discusses this generation’s “Biggest Disruption” nobody mentions that it will be the approach to software design and implementation)

And now for the implausible new plan!

I’ve been sitting on game designs now since before the baby Cobra arrived (the first one) and the game idea that I really like right now is the one that requires the least amount of artwork. It’s the one that relies on emergence more than the others, it’s the one out of which endearing gameplay falls out of a simple underlying model. It’s kinda groovy in a “not been done before” sort of way, I think.

However, the road to failure is littered with half-finished things and before giraffes grace your device’s screen (yes, giraffes! It’ll be so cool!) there’s something I need to finish. Game number 1, therefore, is now engine-complete. Here’s the Table O’ Progress:

| Estimated total project duration: | 4 months with a month’s contingency |

| Start date: | March 2010 |

| Total progress so far: | Twelve weeks |

| Total progress since last update: | Nine weeks! (75% complete!) |

| Estimated completion date: | Maybe even this year! |

That’s right, folks, how about that? Four years down the line, I’m finally code complete. I’ve got no known bugs (but then again, my QA department is my eldest daughter and she enjoys the attract screen much more than the game itself). I’m down to some graphical stuff, some audio and level design. It’ll be the latter of those that drags on, but (and you’d better screenshot this because I’ll be back in a few weeks to “edit history” in my favour) my current aim is to publish on the 14th July 2014. And it’s going to be free, mostly because that’s probably what it’s worth, but I’ll let self-entitled Internet reviewers be the judge of that… which gives me ten or so weeks to fit a couple of weeks of work and some level design, visuals and audio in.

If you fancy being a beta tester and you have any iOS Retina device, drop me a line. Given my previous success in predicting progress, it could well be the only chance to play my game. Ever.

—

1 “Yes, we’ve selected people from the whole demographic that we believe will play your game”. Sitting behind the one-way mirror watching their baffling selection of L.A. inhabitants look at the computers muttering things like “what’s this?” whilst holding a mouse would have suggested otherwise.

2 This actually happened. Apparently it would “get us in the mood” to be creative. It didn’t.

3 And so did this. Apparently, everything fitted into these four magical boxes, including our product. Worst. Trip. Ever. I tried to drink enough to forget, but memories of it still burn my eyes.

Book Club episode II: Wool and the art of software documentation

Occasionally, but just occasionally, you end up reading a book that is so good that you can’t stop talking about it to all of your friends. It weaves a story of such magnificence that you’re on the verge of stopping perfect strangers in the street in order to check if they’ve had the pleasure yet. Wool, by Hugh Howey is one of these books.

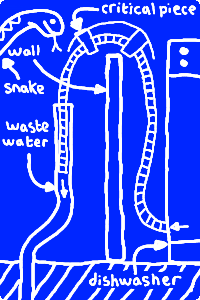

Honestly, my pictures just get worse and worse. Here’s a snake who looks good out of one eye, but pretty skeletal out of the other. I wonder why. But “I’ve said too much already”, etc.

I finally caved during the summer of 2012 to bring a welcome halt to the non-stop nagging I’d been receiving from a friend. I’ll just say this: of all the books I’ve ever been talked into reading, Wool is – by a Norfolk country mile – the best call and I’ve been talked into some crackers. Almost every nook and cranny of the Internet has something about Wool these days, but in the highly unlikely event that you’ve not heard of it or have not had the pleasure yet, you should do so. You’ll not regret it. But let me jump ahead of myself briefly: my friend introduced it as “It’s set in future. People living underground. Lots of strict rules. One in, one out. But I’ve said too much already.” And I tell you, if there’s one phrase that you hear a lot from people trying to talk you into reading Wool, it’s “I’ve said too much already”. Of course, once you’ve read it, you’ll understand just how right this is: don’t do too much research because you seriously don’t want this story spoiled. Resist the temptation. Don’t let your curiosity tarnish something really, really special: incredible depth that just keeps on giving, page after page.

Lots of books, including bloody amazing ones like last time’s book club star, the Pillars of the Earth, reveal their setting’s overall scope at the outset. Very early on, sometimes even from the back of the book alone, you know the entire theatre in which the story will take place. The plot, of course, winds, twists and turns but massive surprise revealings that transform the story’s universe don’t happen. Wool, though, well, words are, as you’ve probably noticed, failing me. It is a book of nested Doctor Who TARDISs that you simply don’t see coming even when you think you do. Take the first half of the opening sentence: “The children were playing while Holston climbed to his death”. This practically grabs you by the balls and begs you to turn the page. Why did he die? Was it an accident? Is he about to be murdered? Who did it? Does he know it is coming? Tell me! TELL ME! Wool positively infects you with curiosity. The words vanish silently into pages as they magically turn in front of you and the story expands in ways you could not have imagined.

Wool: achieving unputdownable status without the need to resort to new branches of physics. Picture credit, The Great Architect, b3ta

If you are a fan of science fiction or simply love stories of great depth that explode gorgeously in unpredictable ways then your life is not complete unless you have read Wool: but, again, heed this one teensy smidge of advice – it is very important you know nothing more than the back cover and frankly, not even that (Random House’s 2013 print says too much, in my opinion, so if you buy it, treat the back cover as though it was the final page – a secret from yourself). You’ll feel richer having read it. If nothing else it will reinforce any suspicions that you may have that IT departments rule the world.

But I’ve said too much already.

Code beautiful: segue warning

Since I’m trying to win this year’s “shit segue” award, I figured I’d try and link this into software development somehow. With my recent post on dishwashers “seamlessly” transitioning into a rant on user-interfaces, I thought I had the award secured – albeit by the skin of my teeth – but this one is a sure winner and shows my awesome potential as a DJ. Wool is a special breed of book: it reads by magic. Your eyes look at pages full of words, but that’s not what you see. What you see is pictures, people, emotions. You’re there. The words somehow lift off the paper and end up forming video in your mind. This makes it an effortless exercise in enjoyment: you’re free to sit back and watch a movie, effectively, whilst holding an actual book with pages that simply reads itself. Few authors can do this and Hugh, to the incredible joy of his bank manager, I’m sure, is clearly one of them.

I knew Wool was special when I read it, but I knew it was really special when one day, Mrs Cobras said “can we go upstairs early and read?”. Way-hey! I thought, clothes falling from my body as I rushed upstairs to the bedroom. Imagine the disappointment when it turns out that this actually meant “can we go upstairs early and read?”. Thus, should I ever meet Hugh Howey, as well as taking my hat off to him, I will buy him a beer, but I specifically won’t enjoy doing it. I just feel I ought to. In a Ned Flanders “good host” sort of way.

Given that this was the first book of the many that I’ve tried to palm off on her that she’s actually read, this represents a major gold star for Wool. She picked every single moment that she could to read a page or two and was utterly hooked. Between that and another friend who sent me three texts (and two e-mails) to say how wonderful Wool was – to make sure I knew that the recommendation was appreciated – it’s clear that like rocking horse shit, clean modern trains in the UK, unicorn horns and good customer service from British Telecom, Wool is not something that you find lying around often.

But Hugh isn’t paying me to kiss his arse, so how does this link into software?

Love is shown in the details

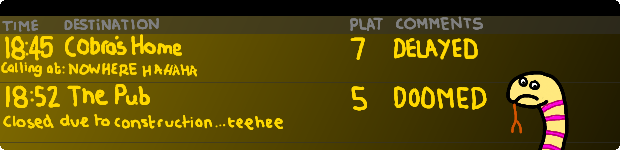

The difference between good and great is the detail. Of course, that can pretty much be said about any place on the scale: the difference between outstandingly shite and vaguely bearable is also in the attention to detail shown. Take these two recent examples from Cambridge railway station:

I don’t know where to begin. I could make a gallery out of these things. Often, trains consist of “8 coa” and are going to “King” and have first class carriages in “carriage 1 &”. For it to be this way for over a year is amazing. This is because it was probably done by the lowest bidder who maximised their profit margins by doing a half arsed job. I’m sure the irony of this is missed on Greater Anglia because they couldn’t care less1.

The lack of detail and attention to quality is of course amazing at first glance until you realise that this is the British Railway system. I am sure that the likes of ATOC, the official turd polishers of the train operating companies, would explain how I am totally wrong in the conclusions that I am drawing here, but humour me anyway. Firstly, these screens are simply not designed to prioritise critical information. If you are in a hurry, often you have to wait for bloody ages to see the piece of information that you require. Secondly, they are poorly laid out: too much detail where there should not be detail and it enough detail where there needs to be detail. Finally, and most unforgivingly, the people who wrote the software did such a fucking piss-poor job that it does not even match the width of the screen. Everything that is important about the special notice is not shown. This is the case with all the data on this screen. And, it has been this way for over a year, thus showing the spectacular lack of pride that everyone involved has in the “service” that they provide. Mere words could not convey how much joy the virtual elimination of commuting has delivered to my life: I died a little bit inside each day I have to give those bum-stands any of my money2.

One of the many things that really, really steams my mirrors is a lack of attention to detail. It shows a messy, untidy mind and just stinks of lack of quality. It also has the mild smell of being done by someone who simply doesn’t care and has no pride in the final delivery. Having worked in software for the best part of a quarter of a century I have had enough opportunities to see such rubbish to write a book on the subject of poorly written code (to be fair, if I step off my moral high-ground briefly, I perpetrated some of that code in my early career). However, each and every page written would raise my blood pressure and I would be dead before I had drafted the first chapter. Instead, I shall bitch and moan in this brief blog post and then go straight to the wine rack and calm myself with a nice castle nine popes3.

Perhaps I just have impossibly high standards or maybe I have been burnt too often to keep making the same mistakes, but I feel that software is not just for Christmas, it is for life. We live in a disposable society and whilst there are signs of that changing, software seems to have taken very well to “knocking it out and throwing it away” as an actual, genuine process: particularly in the games industry. Sometimes the blame can be portioned off the twin evils of software development Mr Schedule and Mrs Specification. Other times, inappropriate process has to step up to the plate: either too much of it, the wrong type of it or–more often than should be the case–absolutely no process at all. Sometimes there is even a soupçon of misused agile around to provide a complete loss of big picture (but by jingo aren’t we cracking through a checklist!). The mistake that many programmers make is to believe that the pie of blame has been fully eaten at this point whereas, in fact, a good half of it is still remaining and that half is theirs to savour and enjoy.

The myth of self-documenting code

Self-documenting code is something that most programmers claim to believe in but few actually do. Many programmers cannot understand their own code just days after they wrote it but still talk about the importance of self-documenting code. Others simply believe that they are doing it and use that as a justification for writing no comments. I believe this: software is a story and you had better tell a good one that you and others can follow or you might as well have eaten a large bowl of alphabetti spaghetti and shat the results into your computer.

If you can’t tell a good story using an appropriate combination of neat code and relevant commentary then the chances are you have written bad code on three fronts: 1) you don’t care enough to make it nice 2) you have not thought it through or designed it properly and 3) there’s probably no good story to tell. And that’s selfish. This means that one day, and possibly one day soon, some other programmer will come across this code, realise that it is awful and be forced to rewrite it and on too many occasions in the first decade of the new millennium, that other programmer was me. If the people paying the programmer are fortunate enough, that person won’t replace one chunk of bloody awful code with another bloody awful chunk of code.

Self-documenting code without suitable commentary is largely a myth. Raw source-code doesn’t contain editorial, thoughts, considerations: it doesn’t explain the why. What was the programmer thinking? When was this done? Why is the algorithm done in this way and not that way? Was it because of a standard library problem? What were the ideas at the time for improving it? Why was this corner cut? This stuff is important and no programmer should have to spend days in source-control trawling the history to figure out basic context. It infuriates me that programmers don’t feel the need to tell a story that they and others can reconstitute with ease down the line: one where the purpose of the code leaps out at the reader along with all the interesting footnotes and commentary that provide context and encourage a relationship between the writer and reader. Remember: one day you could be that reader.

Software life-spans demand exposure of intention

32 bit Unix systems, and they are plentiful across the globe in everything from power stations though ticket machines, trains and appliances, represent the date as “seconds since 00:00, January 1st, 1970.” in a signed 32 bit integer. This means that the maximum number of seconds it can store is 232, which translates to 3:14.07AM, Tuesday 19th January 2038. One second after that, it will roll over to zero. Any code that uses “greater than” or “less than” on a time value at that point will stop producing correct results. And if you’re in any doubt that today’s computers will be in operation in the year 2038, think very carefully when you’re on a train built in 1975 or powered by a power station built in the 50s, 60s or 70s.

Code without comments shows function, but not intention. That’s something you’ll appreciate if you’ve ever waded through code that has fantastic layout, amazing, readable variable names, cracking function names but is still frustratingly challenging to figure out enough of the “what” and “why” just so you can make one, small modification that would’ve taken five minutes if the original author had just had the decency to slap a couple of lines of text in describing the code’s intention. Of course, one could always write a specification or some separate documentation, but out of la-la land and back in reality we all know that isn’t going to fly. Separate documentation is rarely finished, rarely updated and usually lost. It’s a waste of time for everyone and good programmers rarely have the time, patience or ability to create wonderful documents. Documentation should go where it is useful to those who need it, which means in and amongst the code itself. It’s easy to update, it tells the right story and oozes context where context is needed.

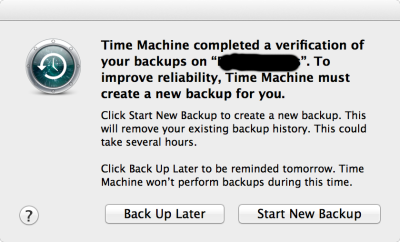

Software’s life-span has an annoying habit of being considerably longer than anticipated which is why there was a Y2K problem in the first place and why there will be a year 2038 problem twenty-five years from now. And that’s forgetting the short-term pain caused by warming the cockles of managers by ticking boxes early in a project with a “we’ll fix it later” attitude that helps explain why the last 10% of so many projects takes 90% of the time: it is in fact 90% of the work and everything up until then has been a barely functioning skeleton of badly documented, poorly structured temporary code interleaved with special cases that just meets the requirements for leaping from one milestone to the next. One could call this “house of cards” development and it leads to more wasted time (and therefore money) rewriting unintelligible code than anyone can possibly imagine.

Everyone has their excuse for banging out disposable hieroglyphics instead of readable software, but my favourite three are “it’s self-evident what’s going on, it’s self-documenting” (hahahahaha!), “I’m in a hurry, I’ll come back and comment it later” (you won’t) or “yeah, but then I’ll have to update the comments every time I update the code” (demonstrating a phenomenal lack of understanding of the very basics of creating narrative). No matter how you wrap ‘em up, though, they are excuses; either ways of disguising bad code through obfuscation of shiteness or rendering good code bloody useless by requiring readers to engage in hours of close examination to find out what’s happening. If it is a beautiful algorithm written with pride then it deserves to be presented as such for all to appreciate for years to come.

Bad programming is just natural selection at work

Of course, the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t always the train coming the other way. Even in the games industry, the onlineification of software is increasing life-spans of code to the point that good, careful design is beginning to become an essential part of the arsenal of weaponry required to stop programmers killing each other as well as ensuring that one doesn’t attempt the futile task of building fifty story tower-blocks on foundations designed for a garden shed. Long-term survival is increasingly dependent on stamping out a fire-and-forget attitude that came from slapping it into a box and shipping the damn thing which up until recently was pretty much where each game’s software story ended (“What? No class-A bugs you say? Ok – everyone step away from their computers. We’re shipping.”).

Code should be beautiful. Your source should be a work of art. The story you are telling should leap from the page out to all the programmers who see it. Maintenance work should be trivial to do: you know the old saying, write your code as though the person who will maintain it is a dangerous psychopath with a desk drawer full of loaded guns.

Make your code read like Wool does. Like a good book, the story should lift effortlessly into the eyes and minds of the readers, because it shows that you care. It shows you’re a good programmer who believes that the quality of what’s under the hood is directly related to the quality of the deliverable.

–

1 Please take note, those of you who get this wrong (I’m looking at you, large portions of the USA), it’s couldn’t care less, not could care less. The meaning is completely different and when you use the latter you’re not saying what you think that you’re saying.

2 But I’m not bitter. No, wait, that’s not right, I am bitter.

3 Don’t worry, I know.