“This is my 22nd year doing this, and every single console transition we’ve seen an increase in development costs. Over long periods of time it gets smoothed out, but I would say this is not a transition where that’s going to be an exception.”

– Activision CEO Bobby Kotick, commenting on the expected rise in costs of development for the upcoming new generation of consoles

Sorry dude, you’re doing it wrong. But don’t feel too bad, you’re certainly not alone. Like so many, you’re looking at methods of managing complexity instead of investing in figuring out how to eliminate it in the first place.

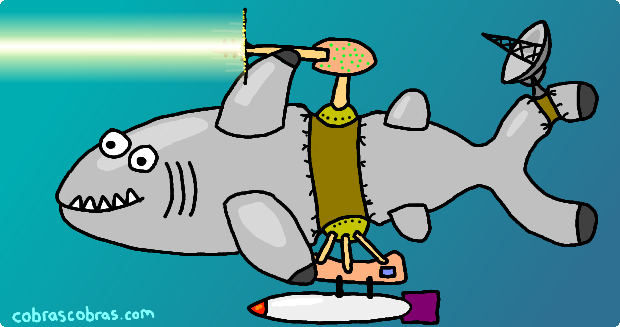

Overcomplicated shark is overcomplicated. He’s OK for getting rid of the odd minor eel infestation, but when it comes to an entire ocean, his single missile/single laser design just doesn’t scale. Cloning him isn’t the answer, he just isn’t an appropriate solution any longer. Software complexity kills software.

When my daughter hides her breakfast cheerios between the sofa cushions, that isn’t solving the problem, that’s hiding it. When mummy and daddy sit down and find the experience crunchier than it should be then the game is over. Right now, every generation of consoles does indeed increase the cost, and therefore risk, of development. Who benefits from this? Beuller? Beuller? That’s right, groovers, nobody. Innovation along with new ideas go straight out of the window in favour of the least possible risk option. Consumers end up with more of the same, but, ironically, less because as fidelity of experience increases, so does the ability to spot how utterly shite computer AI and world dynamics really are. Besides which, the fire exit might look pretty, but as was the case in that Simpsons episode, more often than not, it’s just painted on. Our always-on (unless BT supplies your broadband, in my experience), online, socially connected world fills modern entertainment experiences with vast numbers of the most unpredictable elements possible – humans – and tries to contain them in a highly specified, top-down construction that can’t possibly keep the trousers of plausibility up forever: and it won’t, despite everyone’s best efforts.

But let’s scale new heights of wrongness with this year’s winner (and by a country mile), one of the commenters to the story I got Bobby Kotick’s sound-byte from. He said… drumroll…

“I believe Microsoft and Sony are irresponsible in bringing technology into an an industry where it is almost impossible to recoup development costs. Development should be simple – tools should be fast and they are not. Tools are very much LAGGING behind technology…”

Do you hear that noise? No, and I don’t either. And that’s because it is the world’s smallest violin playing just for the author of this comment. I have not laughed so much since I tried gas-and-air when Mrs Cobras was about to give birth to Baby Cobra (just to test it for safety, obviously). If ever there was a more clearly illustrated detachment of cause and effect, this is it. The manufacturers? Irresponsible? They’ve given you hardware of incredible, awesome power and all the tools you need to do stuff with it. The rest is your problem, not theirs. My heart bleeds for your complete, comprehensive failure to figure out how to manage software complexity properly. Developers are reapplying the same tried and tested methods, tools and processes that worked well when life was simpler and had fewer bits, bytes, bobs and threads and acting all confused-like when it doesn’t scale. I add vanilla essence to my cake mix with a teaspoon but would I wouldn’t fill a swimming pool with one (I’d use a dessert spoon, obviously). How does this chap get to work? On a plank carried on the backs of a million ants?

Let go, Luke, use the force…

If complexity is a problem, and it quite clearly is, then instead of working out how to manage that complexity, work out how to do it with less in the first place. Something with less “agile” in it where the computer, which is, after all, capable of billions of operations per second, actually does some of the work for us. And this, I humbly offer, is where bottom-up, nature-inspired model based solutions have so much value: develop seeds, get the jungle for free. It’s the Lego of software design — create life support systems for small, simple systems and allow an incredible web of beautiful complexity to emerge. As a programmer, this is gorgeous: I need not know how to solve the problem in order to solve it, I merely create and environment where those problems can solve themselves.

The crying shame, of course, is that somewhere in their hearts programmers know this. They embraced dynamics models to make their cars, bikes, tanks and helicopters behave better yet the extra step of architecting entire engines this way eludes them. Ultimately, it’s scary to not have control: bottom up development philosophies trade predictability and understanding for simpler, more reliable – but mysterious – solutions. Don’t underestimate the requirement for having control: it’s the foundation of traditional design, scheduling and programming that puts the pipe and slippers onto developers world-wide. It is frightening to answer any question with “emergence” or “I don’t know how it will work, but it will” and designers generally hate it: you can’t script such a beast, you merely guide it. Management and investors don’t like being bathed in variables and even where risks are taken, those risks need to be mitigated better than “trust me, this’ll work”.

It’s a pity that few are ready to take the leap of faith that true bottom-up emergent simulation engines require because believability and suspension of disbelief come from the grey areas. The details. And it’s details that are expensive to produce: the production of millions of possibilities and variations where most people only see a small fraction. To create so much software and expose the average user to so little of it might be considered wasteful. If nature had built our brains that way, they’d be the size of a planet and wouldn’t work. Creating software that adapts itself to the needs, desires and demands of the person using it would seem on the surface to be a far more efficient method of development.

Not just hot air, just mostly hot air

It’s more impressive than it looks. It’s constructed, on-demand, with nothing but a massive cash-in on nature’s 3.7 billion year R&D program

But — and as usual, this isn’t the nice ‘but’ with two ‘t’s — this was an era before easy self-publishing, when Apps were called “Applications” and it required an enormous amount of money and resource to bring a product to market. Of course, that’s not to say we had the right product anyway, because if there was one thing that we were world-class at back then in the mid naughties it was disagreeing with each other. World class. It’s fun to imagine alternative realities, so long as we first brush aside the obvious fact that if ifs and buts were sweets and nuts it would be Christmas every day. Perhaps if we’d had the wonders that social media brings to marketing and community building as well as a route to getting products that we’d built with this technology directly to devices and consumers as an iterative affair then things would be different. But maybe not. Sometimes there is a time for these things and maybe then wasn’t it.

However. Maybe now is. Exciting things are growing…

… figuratively and literally.

Isn’t that nice?

One Response to Overcomplicated shark is overcomplicated